Homomorphic Encryption

Table of Contents

Introduction to the Problem:

Consider a company that needs a dataset to be processed by a third party. That dataset contains customer data so it needs to stay confidential. A breach of this data could lead to catastrophic consequences, jeopardizing the company's integrity and reputation. We could employ secure transmission by using asymmetric encryption, a robust method involving a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption. However, this approach partially addresses the issue, as the data must still be decrypted for processing, leaving a window for attacks and leaks when the data is decrypted. Furthermore, This necessitates placing considerable trust in the third party, a significant concern under strict privacy protection and compliance regulations.

In response to these challenges, homomorphic encryption offers a sophisticated solution. Homomorphic encryption allows you to perform calculations on encrypted data without first decrypting it. This guarantees data secrecy throughout the process. The decrypted results are identical from what would have happened if operations had been performed on the original unprotected data.

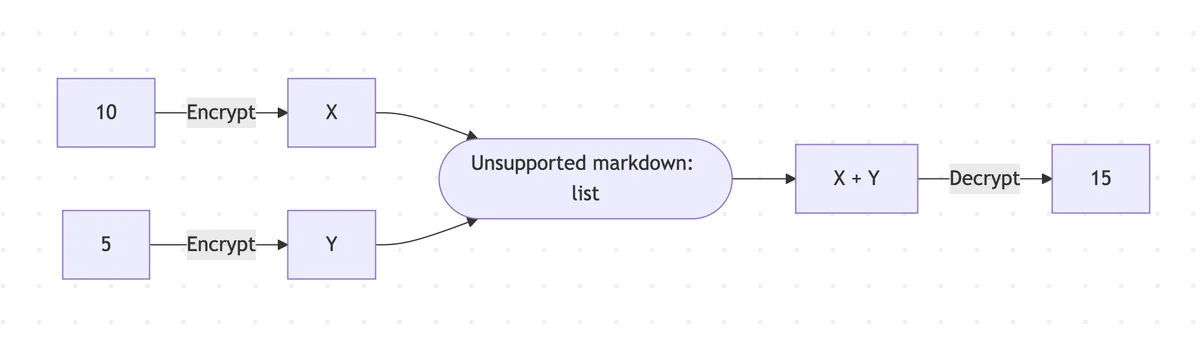

Here is a simple graph explaining a homomorphic encryption scenario:

Real-World Applications:

Homomorphic encryption (HE) plays a crucial role in various sectors of the digital landscape. Here are some fields where HE is prominently used:

- Cloud Computing: HE allows users to securely outsource storage and computation to cloud services without compromising the privacy of their data. This is particularly relevant for businesses that handle sensitive information but rely on cloud platforms for data processing and storage.

- Healthcare Data Analysis: In healthcare, HE can be used to analyze encrypted patient data for research and treatment purposes without exposing individual patient information. This is crucial for complying with privacy laws and regulations.

- Secure Voting Systems: HE can enable secure electronic voting systems where votes are encrypted and tallied without revealing individual voter choices, ensuring both privacy and integrity in the voting process.

- Financial Services: Banks and financial institutions can use HE for encrypted data analysis, like risk management and fraud detection, without exposing individual customer data.

- Personalized Advertising: HE allows companies to tailor advertisements based on encrypted user data, ensuring personalized marketing without compromising user privacy.

Types of homomorphic encryption

Homomorphic encryption comes in several types based on the nature and extent of operations it supports:

- Partially Homomorphic Encryption (PHE): This type supports an unlimited number of operations, but only of a single kind, either addition or multiplication, on the ciphertext. These schemes are simpler to implement because they focus on a singular operation.

- Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption (SHE): These systems are more complex and permit a finite number of either addition or multiplication operations. Unlike partially homomorphic encryption, which allows infinite repetitions of one operation, somewhat homomorphic encryption limits the number of operations but can support both types within that limit.

- Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE): The most advanced type, we can do an unlimited number of both addition and multiplication operations on ciphertexts. This versatility means that any program can run on encrypted data, yielding encrypted outputs, without ever needing to decrypt the inputs.

Here is a table that explains the different types of homomorphic encryption in a simplified manner:

| Type | Actions | Number of Operations |

|---|---|---|

| Partially Homomorphic Encryption | One (Addition or multiplication) | Unlimited |

| Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption | Two (Addition and multiplication) | Limited |

| Fully Homomorphic Encryption | Two (Addition and multiplication) | Unlimited |

Intricacies and Math

For simplicity purposes, We are going to use a straightforward SHE encryption scheme that utilizes basic modular arithmetic and uses Gentry)'s techniques (more on that later) to convert it into a fully homomorphic scheme. This was taken from Fully Homomorphic Encryption over the Integers

We start by picking:

- A large, odd number p to be the secret key.

- A large, random number q (for each encryption).

- A small, random number r, also called noise (for each encryption).

Note that the public key is qp + 2r.

The noise mixed into the encryption ensures the system's security by adding random small values, like numbers or polynomial coefficients that could be -1, 0, or 1. This randomness means the encryption method is based on chance, although there are other random factors in play as well, not just the noise.

Encryption

Consider a bit b (0 or 1). To encrypt, simply compute:

Decryption

To decrypt ciphertext c, simply compute:

We do c mod p to get 2r + b, then we reduce mod 2 to get b.

HE Addition

Consider two ciphertexts. To add, simply compute:

The noise increases linearly with addition.

HE Multiplication

Consider two ciphertexts. To multiply, simply compute:

The noise increases exponentially with multiplication.

Noise

In an encryption scheme, the noise 2r must not exceed half the value of p to ensure accurate decryption. When the noise surpasses p/2, decryption becomes unreliable. Without a strategy to manage or reset this growth, the number of operations becomes limited—numerous additions are possible, yet multiplications are few before reaching the critical noise threshold of p/2.

The limitation of SHE is its noise constraint. For FHE, it's necessary to periodically reset the noise as it approaches the maximum threshold.

One simple method would be to decrypt the ciphertext and then re-encrypt it, effectively resetting the noise level and allowing more homomorphic operations. However, this method is impractical as it requires decryption, undermining the primary purpose of homomorphic encryption.

In 2009, Gentry proposed a solution where he converted the decryption algorithm into a homomorphic computation. By processing this with the ciphertext and a version of the private key that is also encrypted, the result is a new ciphertext corresponding to the original plaintext, but with less noise. This process of noise reduction is known as bootstrapping and marked the inception of the first FHE scheme.

FHE Schemes

FHE has undergone significant development over the years. The table shows the different FHE schemes.

For a more detailed comparison, you can read "FHEBench: Benchmarking Fully Homomorphic Encryption Schemes".

| Feature | Gentry | BGV | GSW | BFV | TFHE | CKKS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year Introduced | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2012 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Key Underlying Problem | Ideal Lattice Problem | Ring Learning With Errors (RLWE) | Learning With Errors (LWE) | RLWE | LWE | Approximate GCD |

| Main Advantage | First practical FHE scheme | Can handle an arbitrary number of additions and multiplications | Simplicity and modularity, suitable for advanced cryptographic constructions | Better for integer arithmetic | Extremely fast for certain operations, particularly bootstrapping | Supports approximate arithmetic on complex numbers |

| Noise Growth | Rapid | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Very low | Moderate |

| Typical Application | Proof of concept | General purpose | Advanced cryptographic protocols | Better for applications requiring integer arithmetic | Real-time encryption scenarios, IoT applications | Suitable for machine learning and signal processing |

FHE Models

Current FHE schemes implement computation in three different ways:

| Boolean Circuits | Exact Arithmetic | Approximate Arithmetic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Handled | Bits | Whole numbers (and groups of them) | Real or complex numbers |

| Operations | All types of logic-gate operations | Arithmetic with whole numbers | Operations like those in floating-point math |

| Special Features | Fast comparisons, quick resets | Group operations on numbers, avoids frequent resets | Good for complex calculations like machine learning |

| Notable Techniques | GSW, FHEW, TFHE | BGV, BFV | CKKS |

FHE Frameworks

Here is a list of current FHE frameworks (libraries) available to use with their supported schemes (as of Nov 24, 2023):

| Framework | Developer | BGV | CKKS | BFV | FHEW | CKKS | TFHE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HElib | IBM | x | x | ||||

| Microsoft SEAL | Microsoft | x | x | x | |||

| OpenFHE | Duality and a DARPA consortium | x | x | x | x | x | |

| HEAAN | Seoul National University | x | x | ||||

| FHEW | Leo Ducas and Daniele Micciancio | x | |||||

| TFHE-rs | Zama | x | |||||

| FV-NFLlib | CryptoExperts | x | |||||

| NuFHE | NuCypher | x | |||||

| Lattigo | EPFL-LDS | x | x |

Final Thoughts

Homomorphic Encryption is approaching a pivotal moment in its application, heralded as the "Holy Grail" of cryptography. Driven by the need for provable security models, emerging post-quantum cryptography (PQC) requirements, and the potential for secure data collaboration, FHE is on the cusp of transforming commercial industries. Its ability to perform computations on encrypted data without exposing sensitive information promises revolutionary changes in data analytics, integrity, and licensing models.

Active research and development, both in academia and industry, are rapidly enhancing FHE's performance and accessibility, hinting at a future where secure computation on untrusted platforms is both routine and reliable. As FHE matures, it stands to redefine secure data processing and sharing, mirroring the transformative impacts of databases, cloud computing, and AI.

Log in to leave a comment.